Leading through a catastrophic crisis

There’s a lesson that every emergency and crisis manager learns about disaster response; that’s the realization that 911 is not showing up. It’s not an expectation but a realization of two things:

- In an actual down situation, you can’t expect the first responders (911) to be around to help. When responding to a major crisis, they could be tied up helping the most vulnerable.

- The other realization is that they may not be able to get to you due to the circumstances.

We saw this during 9/11 and natural disasters like Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy. As resilience professionals, we know that the lack of available rescue and disaster recovery services is a real risk. Any of us worth our salt are advocates for planning and exercising for worst-case scenarios. However, what is less well trained is our ability to lead through a crisis.

So, this blog focuses on aspects of leadership we must develop to become believable through a catastrophic crisis. It’s an aspect I see missing in our training. There are fundamentals like the BCI’s Incident Response & Crisis Management course. I spoke about the importance of hard and soft skills in the Diversity In Disaster Management blog. These are good but aren’t the type of practice needed to lead through an extreme crisis.

Learning from failure and success

My inspiration for this came after watching a recent episode of the Shawn Ryan Show, Vigilance Elite, where he interviewed navy seal Jason Redman. Leveraging extraordinary vulnerability, Redman, now a motivational speaker and coach talks about how his failures in life drove him to overcome personal demons. There’s a lot more to his story, and I recommend his books, starting with The Trident. It describes his “humble journey of evolution and lessons learned through supreme challenge, complex adversity, and near-death revelations that forged and re-forged the spirit, success, and ongoing mission of a U.S. Navy SEAL leader.”

Now, I was fortunate to learn from leaders in emergency management and the Red Cross, many of whom were former military or law enforcement. However, the nurses and medical professionals working alongside them were just as skilled. Finally, I also saw those with no prior specialization rise to the occasion numerous times when the situation required it. The difference was either the former experience or training, including involvement in large-scale exercises. Although the history of crisis management is that leads often came from militaristic disciplines, we can’t rely on this foundational training for future leaders in this space.

Supporting the next generation

That’s why I advocate for greater emphasis on preparing the next generation of new crisis managers. Crisis response is serious business, often physically and emotionally draining. It requires the skills of remaining calm under pressure and good decision-making, often with incomplete data. Yet, I rarely see exercises where leadership steps out to train junior or new personnel.

I’m a fan of the International Crisis Management Conferences (ICMC) and Rob Burton. Yet, reviewing their current ICMC Training Courses displays no higher-level training for leaders. And yes, not having taken all of their courses, I’m confident skills are shared. It’s not just the ICMC; looking at the Business Continuity Institute’s (BCI) offerings, there’s a CBCI Certification Course for BCM Managers. Again, aspects get included, but nothing on the roster explicitly teaches leadership in the crisis space. To The DRII’s credit, they offer Mindfulness Practices to Improve Incident Management, but that’s it. There’s a gap in practice to expect every crisis manager to step into the role with the right attributes fully baked in.

On-the-job training and experience is not enough

What resonated from Jason Redman’s conversation with Shaw Ryan (a former navy seal himself) was his focus on learning as much from failure as victories. It was also his emphasis on the fact that in the heat of battle, 911 is not showing up. As trained as our military personnel is, they understand there are situations when the cavalry (back-ups) can’t get to them. So, I ask my fellow crisis managers-how prepared are you to lead your organization if a situation is so bad that no reinforcements are coming to help your organization?

And yes, I know that most of us come from military, law enforcement, NGO, or related disciplines into a crisis role. However, we can’t rely on future leaders to take that route. More and more, I see colleagues voluntold or providing opportunities within their companies to take a lead position. Doesn’t it make sense to offer more than on-the-job training by letting them flounder through events? Leadership, as I am learning, is an art and often not very well taught. Learned as much as inherent, we can do a better job of teaching leadership principles.

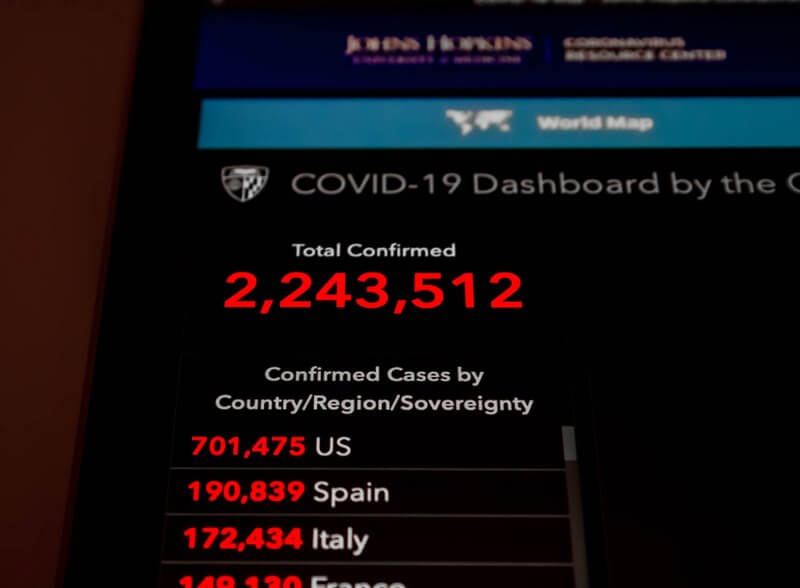

We are already experiencing the increased intensity of natural disasters and their impacts on communities and economies. Geo-political risks are ever-increasing. The COVID pandemic displayed how vulnerable we are worldwide. And, responding to concurrent events is on the rise. As a community, resilience practitioners must better prepare for events. It’s not a simple side-arm of business continuity planning but a discipline. Crisis and resilience leaders must transform into principal players of their leadership teams.

Developing the crisis leaders of the future

So, understanding that 911 is not showing up in extreme cases, what can we do to prepare our future crisis leads better?

Here’s a list I brainstormed:

- Create bespoke training for crisis leadership. It should go beyond teaching hard and soft crisis response skills, although that is vital. It must also teach the less-defined skills of succeeding as a leader in a corporate or nonprofit environment. I recently had the privilege to hear Jeff Shannon speak about being believable at work, describing the importance of developing an effective leadership presence. His book, Hard Work Is Not Enough, describes strategically becoming more influential.

- We must create training and exercises for crisis leadership. On the public side, FEMA offers an Advanced Professional Series (APS). It also provides a National Emergency Management Executive Academy focusing on Strategic Leadership and Critical Thinking. Although helpful, it misses the corporate aspect of leadership.

- Consider coaching or mentoring for crisis managers. Again, programs exist within BCI or the DRI for general mentorship, but I am unaware of targeted programs. Companies and universities like Harvard offer programs for leadership development for high-potential leaders. Let me know if you are offered these opportunities as crisis leaders in your companies. My guess is not. Crisis leaders should get these opportunities, too.

- Champion authentic leadership. Leadership is not synonymous with perfection. The most successful leaders share learning from their failures as much as successes. In our space, much is to be learned from missteps as to what works well. That’s what people like Jason Redman convey, hoping others don’t take the same path. Check out his principles for leadership; it’s inspiring.

- Support the rise of Chief Resilience Officers. Some companies and the US States are already doing this. A Chief Resilience Officer focuses on effective responses when those risks become real. More importantly, the two positions complement each other and work hand-in-hand [Risk Officer] (Patty Pelingon, Insitute for Sustainable Development, Feb 4, 2022)”. The development of this role speaks to the requirement to raise the profile of crisis managers and resilience practitioners.

Call to action and last thoughts

Now, realizing that 911 is not showing up is the first step to developing executive presence. If you are already there and have a seat at the leadership table, that’s great. Share and mentor others coming into the field. Take up the mantel to lift-up others–new personnel or seasoned professionals you see struggling. President John F. Kennedy said: “No American [one] is ever made better off by pulling a fellow American [person] down, and every American [one] is made better off whenever any one of us is made better off. A rising tide raises all boats.” We need to support each other with the highly uncertain future ahead of us.

None of us is a superhero, but we need to raise the level of the profession for all resilience practitioners. Our service is critical to ensuring business success, mitigating risk, and limiting damage. It’s time our senior leaders recognize our value, but it is up to us to do the hard work of leading the charge. In a time with BCM is especially in demand, now is the window of opportunity to ask more from management and ourselves. Resilience cannot exist without authoritative direction and support from those orchestrating the work.